Read the compiled findings from The Relevancy Project in Landmarks Illinois’ November 2023 publication, “The Relevancy Guidebook: How We Can Transform the Future of Preservation.”

The Relevancy Project: Storytelling and Preservation Go Hand-In-Hand

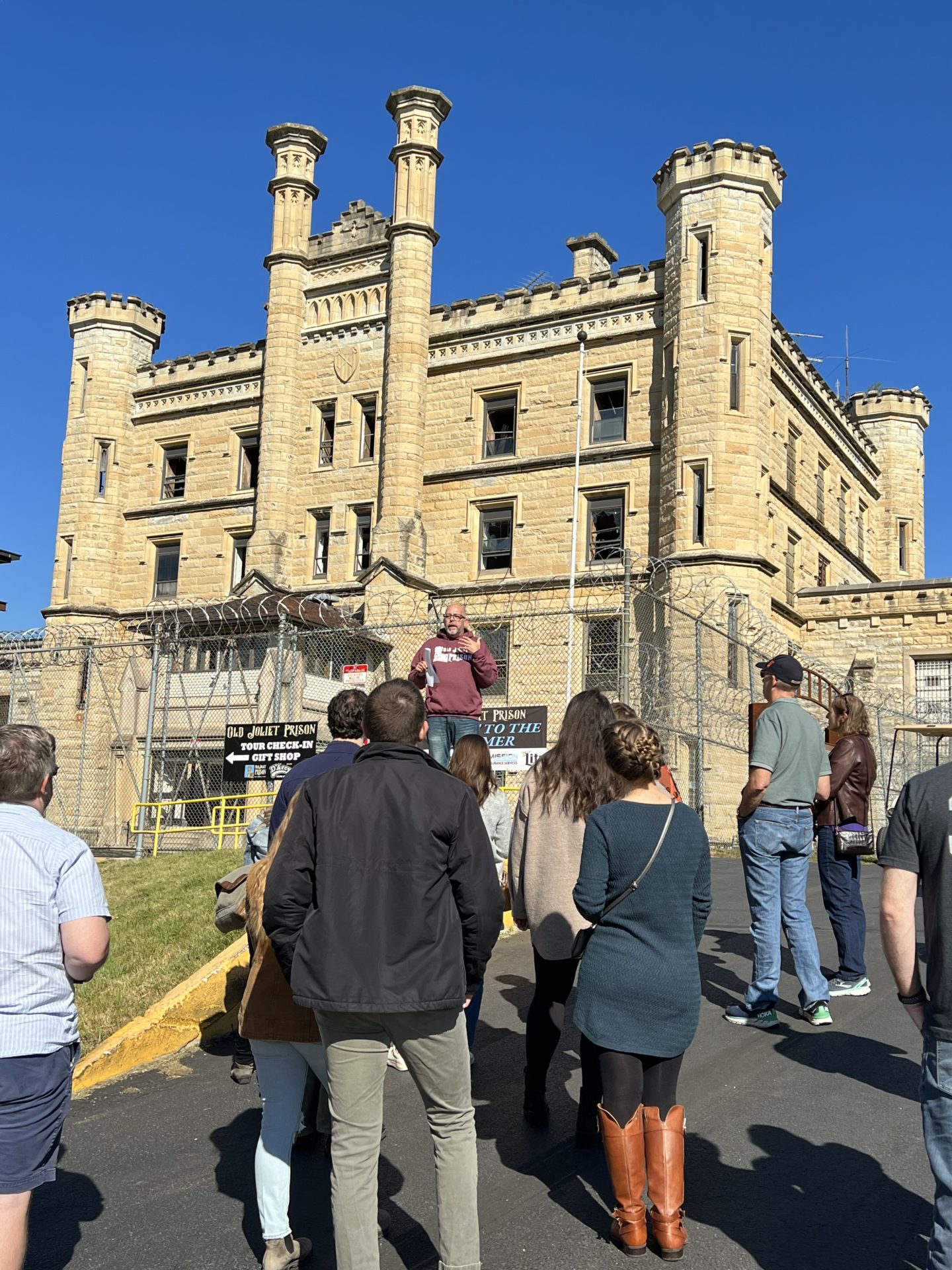

Pictured in the center, Landmarks Illinois’ Regional Advocacy Manager Quinn Adamowski begins a tour of the Old Joliet Prison in Joliet, Illinois on October 1, 2022. While the prision is well known for being featured in the 1980 film, “The Blues Brothers,” or the recent television series, “Prison Break,” Adamowski’s interpretation focuses on the prison as a site of conscience. The prison site, active from 1858 – 2002, is used to inspire discussion about the harms of mass incarcertaion and the need for criminal justice reform. Rather than focus on the buildings’ architects, dates of construction or style types, Adamowski engages the audience through people’s stories with themes we can all relate to: freedom, justice and quality of life. Adamowski chairs the Joliet Area Historical Museum, which manages the prison site.

*You can scroll to the bottom of the webpage for a PDF version of this post.

OCTOBER 14, 2022

BY BONNIE MCDONALD, PRESIDENT & CEO, LANDMARKS ILLINOIS

Jennifer Meisner

Historic Preservation Officer

King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks – Historic Preservation Program

November 14, 2019

Seattle, Washington

A group of 30 third graders sat waiting for my tour to begin. Their heads swiveled back and forth excitedly as they took in the overwhelming interior of the Minnesota State Capitol. It was my job as their tour guide to make sense of what they were seeing. I dutifully followed my script that peppered in dates of construction, architects, materials, symbolism and facts about our past legislators. As our hour went on, the fidgeting increased as the listening decreased. I was discouraged when my amazing facts about the building’s 20 kinds of marble did not excite them. Of course they didn’t, because nine-year-olds don’t have the life experience to provide the context for why facts like this have meaning. Though I was sharing my knowledge, they were no more knowledgeable at the tour’s end. The facts I shared were meaningless without the context to understand the information. It is easy to ignore something you find meaningless. I had the opportunity to spark curiosity, and a love for historic places, in these kids. Instead, they may have grown into adults who find history and historic places boring.

Self-proclaimed history-hating adults that I have talked with, who went through the U.S. K-12 school system, often blame their history teacher. The instruction method is more likely the culprit than the instructor. U.S. history pedagogy puts facts before meaning. Students memorize and regurgitate events, places, dates and names, or at least this is what many adults recollect from their history courses. How many retained the information that explains the systems that live within, or that we are fighting against? We do not remember what we did not understand and we cannot value what we have forgotten. How do we make preservation more relevant to more people? We need to start with how we share our knowledge: tell a great story.

Chere Juisto

Former Executive Director

Preserve Montana

September 18, 2020

Helena, Montana [via Zoom]

WHY IS STORYTELLING IMPORTANT?

Study the cognitive science of storytelling and it is a truly brilliant knowledge-sharing device. Storytelling has been a principal information delivery system for most of human history and, although methods differ, storytelling is universal to all of the world’s cultures.[1] Why is storytelling brilliant? Because it stimulates long-term memory-making in several ways. First, a great story captivates and entertains us. Neuroscience research shows that when we are having fun, our brain “associates reward and pleasure with information, strengthen[s] and broaden[s] memory networks” and taps into both our attention-focusing and mind-wandering neural modes.[2] Because having fun puts us in a good mood, this produces dopamine that enhances the brain’s ability to focus on the information, “reinforces the memory and makes it easier to remember.”[3] Storytellers also employ mnemonic techniques that create associative pathways in the listener’s brain to remember and recall information, including visualization, rhyme and rhythm.[4] Repetitive storytelling included in rituals and ceremonies enhances long-term storage and avoids the brain’s active dumping of useless information.[5] Listening to stories as part of a shared social experience further reinforces feelings of happiness through the release of dopamine and humans’ universal desire to belong to a group.[6] When we tell a story about people and historic places that is entertaining and introduces or reinforces knowledge, especially in a group setting, we create valuable, memorable and emotionally beneficial experiences.

Erica Avrami, PhD

James Marston Fitch Assistant Professor of Historic Preservation

Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation

January 15, 2021

New York, New York [via Zoom]

WHAT MAKES A GREAT STORY?

Historic places have incredible stories to tell, but we need to be their storytellers. As noted in Blog Post #4, people cannot see stories by looking at a place. There are often layers of history, as well, which make a place’s stories more interesting, but perhaps more difficult, to tell. Telling a great story takes work. It is far more than simply providing information. The American Press Institute tells journalists that a great story makes important news interesting and that the news’ treatment trumps the topic.[7]

A great story has a number of vital components. In a 2012 TED Talk, Pixar filmmaker Andrew Stanton shared his method for crafting a compelling, heartwarming story like “WALL-E” and “Finding Nemo.”[8]

1. A compelling story makes you care.

2. A strong theme runs through the story.

3. The story promises to lead somewhere.

4. The storyline is not predictable. Change is fundamental in a story because life is always changing.

5. The audience has to work a little through deductive reasoning.

6. The story evokes wonder in the audience and holds them still.

7. The ending is uncertain.

8. Your main character is likable.

9. Characters have something that drives them.

10. A great story deepens our understanding of who we are as human beings.

11. Our stories should express our personal values.

Filmmakers at Stillmotion have a Vimeo series about storytelling’s four P’s: places, people, plot and purpose, which may be easier to digest and remember than Stanton’s list above.[9] However, both are helpful when considering how to create and share your historic place’s stories.

Emilio Padilla, AIA

Project Director

JGMA

March 13, 2020

Chicago, Illinois

LEARN HOW TO TELL A GREAT STORY

Preservation training does not include storytelling. Professional degree programs train us to conduct archival research and to write historic significance case statements. Though we may read these as compelling stories, the public does not. Period of significance, architectural styles and character-defining features are preservation jargon. Basing a tour around these details is a surefire way to make people feel like outsiders.

Preparing a relevant story requires knowing your audience, their interests and their level of knowledge. For example, my third-grade tour goers knew little to nothing about how many kinds of marble are typically in a historic building. Twenty kinds of marble could be typical, for all they knew. However, a group of tourists who have visited many state capitols would understand that this fact is quite extraordinary. Knowing the audience will guide what information you include and exclude. Storytellers have to choose what they can and cannot share in the allotted time. What is enough information to provide context and meaning, and pique the audience’s interest for more, but not overwhelm them?

How do you prepare if you do not know your audience? Prepare stories that have universal narratives that appeal to anyone. We can connect to our shared humanity through stories of family, home, food and drink, personal, cultural and artistic expression and larger concepts like heroicism, fairness and ethics. These facets of life help to shape our identity and are deeply personal. Connect the humanity of people from the past with those in the present. Tell their stories of challenge and triumph, which we can all relate to. Memorable, relevant history is relatable and something a person can learn from to use in their own life.

Bryan Lee, Jr.

Design Principal

Colloqate

January 21, 2020

Chicago, Illinois

MEETING PEOPLE WHERE THEY ARE

We can make historic places more meaningful to people if we tell better and more memorable stories about them. Remember that for preservation to be relevant to a person, it must be something that: 1) they care about; 2) is useful to them; and, 3) that they want to do something about. Several interviewees for The Relevancy Project emphasized that preservationists need to communicate better about the work that we are already doing. As Nina Simon said in her “Art of Relevance” TED Talk, we cannot be relevant by fiat.[11] We must educate ourselves about and adopt the language and methods that reach, engage and resonate with new audiences. Preservationist and communications expert Cindy Olnick, former Los Angeles Conservancy communications director, has written about this need to reframe preservation. She is currently writing about how her thinking on this topic has evolved and if this blog is available before The Relevancy Guidebook is published, the new link will be inserted. Otherwise, please check her website for updated posts. Once again, this is about preservation changing our practices to meet people where they are and not turning the volume up on what we are already doing.

My unremarkable performance as a historic site guide taught me the importance of storytelling. I took storytelling and improvisation classes at The Second City in Chicago and they have served me well as a frequent public speaker. If you are looking for storytelling resources, please reference the list below. Start with perfecting your story of why you are a preservationist. Your entertaining and informative story might just change people’s minds about history and build future advocates to sustain our historic places.

STORYTELLING RESOURCES

- The 99% Invisible podcast focuses on stories that reveal the process and power of design and architecture.

- The Moth promotes the art and craft of storytelling to honor and celebrate the diversity and commonality of human experience. See their “Storytelling Tips & Tricks.” The Moth recently published a book, “How to Tell a Story: The Essential Guide to Memorable Storytelling from The Moth,” by Meg Bowles, Catherine Burns, Jenifer Hixson, Sarah Austin Jenness, and Kate Tellers. (Available in audiobook or hardcover.)

- Preservation Maryland’s long-running podcast, PreserveCast, engages people inside and proximate to the preservation field to tell their own stories.

- Save As: NextGen Heritage Conservation podcast provides stories about the future of the heritage conservation field.

- Cheap Old Houses™ on Instagram tells the story of, and promotes, old house real estate listings at “cheap” prices. Cheap Old Houses has 2 million followers and has a corresponding HGTV series featuring founders Elizabeth and Ethan Finkelstein.

- Preservation Buffalo Niagara (PBN) are some of the best preservation storytellers that I have seen. Their well-curated social media platforms focus on making their work accessible to others. For example, during the pandemic, Christiana Limniatis, PBN’s Director of Preservation Services, developed a series of short, virtual Instagram reels about historic architectural styles and her favorite walking tours. Christiana’s fun, approachable storytelling method focused on providing meaningful context and not simply the facts (dates and architects). You can still find these reels on PBN’s YouTube page.

- Shermann “Dilla” Thomas, a Chicago urban historian uses TikTok as his storytelling platform and has almost 96,000 followers.

- Georgetown University’s certificate program in social impact storytelling

- EdApp has a list of “10 Free Storytelling Classes,” though five of them charge a fee. Note: I have not used or reviewed any of these resources, but provide them as several free options.

- “Storytelling in Preservation.” Panel Discussion Vimeo Recording, National Preservation Partners Network, undated. Accessed October 3, 2022.

- Atlas Obscura promotes curious and wondrous travel destinations that are not typically in the guidebooks. Atlas Obscura’s contributors write interesting stories about the listed sites to compel you to check them out.

- Cindy Olnick Communications on Reframing Preservation.

- “Storytelling Tips & Tricks” by The Moth.

- K. Kennedy Whiters’ unRedact the Facts™ and blog, unredacthefacts, is a multifaceted call to action by a Black woman architect and preservationist to use active, accurate and complete language and grammar in all forms of storytelling about enslaved Black people and their White enslavers. Using passive voice is a way to perpetuate white supremacy. The call to action also brings needed attention to proper attribution. When activism influences your actions, as K. Kennedy Whiters has done for my own blog post, properly attribute who influenced your thinking and behaviors – and tell them that it has done so. The following is how Vu Le of the Nonprofit AF blog attributed Whiters’ advocacy and intellectual property: “I want to give thanks and credit to K. Kennedy Whiters, Architect and Founder of unRedact the Facts, for giving me feedback and wording to revise the above two paragraphs.” #CiteBlackWomen, #theActiveVoiceIsMyLoveLanguage, #theActiveVoiceIsOurLoveLanguage, @unRedacTheFacts and @CiteBlackWomen

- Zines are short, self-published works to present one’s perspective on a topic. Indow Window hosted a “How to Make a Zine: Historic Preservation Stories,” panel discussion in May 2020. The panel discussion is available on YouTube. Indow has an entire resource page on how to make zines for community communication.

Podcasts

Social Media

Training

Webinars

Websites

Zines

YOUR INPUT IS VITAL

Your thoughts on this and forthcoming topics are not only welcomed, they’re imperative to ensuring this project is inclusive, with well-considered outcomes. So post away on my LinkedIn or Twitter accounts, or send me an email at bmcdonald@landmarks.org. I’ll collect and consider your comments to inform future blog posts and the project’s outcomes published in the forthcoming Relevancy Guidebook to the U.S. Preservation Movement (working title).

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- Do you feel that storytelling is how preservationists should convey the importance of place? Why or why not?

- Think about a great storyteller in your life. What are some of their memorable stories? What made them memorable?

- Would you consider yourself a good storyteller? How do you know? What would others say?

- What training would you need to be a more confident storyteller?

STAY TUNED FOR BLOG POST #11: FUNDING PRESERVATION’S EVOLUTION

FOOTNOTES

[1] Though we do not consider Wikipedia to be a primary source, I do recommend the storytelling page for a thoughtful review of the world’s diverse storytelling devices, from tattooing to tree carving. “Storytelling.” Wikipedia, last edited September 2, 2022. Accessed October 8, 2022.

TED also published an article featuring eight storytelling methods from across the globe. See Amy S. Choi’s “How stories are told around the world.” IDEAS.TED.COM, March 17, 2015. Accessed October 8, 2022.

[2] Shukla, Aditya. “Why Fun, Curiosity & Engagement Improves Learning: Mood, Senses, Neurons, Arousal, Cognition.” Cognition Today, August 23, 2020. Accessed October 8, 2022.

[3] Ibid.

[4] “Memory and Mnemonic Devices.” PsychCentral, last medical reviewed on March 30, 2022. Accessed on October 8, 2022.

[5] Purtill, Corinne. “The New Science of Forgetting.” TIME, April 28, 2022. Accessed on October 8, 2022.

[6] “Social Science 101: This is Your Brain on Social.” Samuel Centre for Social Connectedness, May 17, 2017. Accessed October 8, 2022.

[7] “What makes a good story?” American Press Institute, undated. Accessed October 3, 2022.

[8] Stanton, Andrew. “The clues to a great story.” TED2012, undated. Accessed October 3, 2022.

[9] Hooper, Riley. “Storytelling the stillmotion way: Part 1.” Vimeo, April 17, 2013. Accessed October 3, 2022.

[10] “Griots” are West African oral storytellers who hold highly respected positions in society as knowledge bearers. For more about griots’ method to share legendary epics, read Hakimah Abdul-Fattah’s “How Griots Tell Legendary Epics through Stories and Songs in West Africa.” The Met, April 20, 2020. Accessed October 8, 2022.

[11] Simon, Nina. “The Art of Relevance.” TEDXPaloAlto, May 4, 2017. Accessed October 8, 2022.

Support our advocacy

Be a voice for the future of our communities by supporting Landmarks Illinois. Our work enhances communities, empowers citizens, promotes local economic development and offers environmentally sound solutions.